In 1957 the "Eisenhower Recession" hit GE with a vengeance. I had 10 years seniority and got a new job assignment in Building 273, the giant steam turbine building, as tool maker in C Bay (one of the "low ceiling" bays). It was on second shift (3:00 PM to 11:30 PM) for foreman Carl Schaefer (brother of famed "rain maker" Vincent Schaefer). His section worked on packing rings - the rings that sealed the steam turbine shaft between rows of "buckets", making the super-heated steam go through the vanes instead of along the shaft. The packing rings were made in segments, usually six. The steel assemblies were put on vertical boring mills and grooves cut in the inside diameters for rolled inserts which were assembled - staked in place - the surplus length cut off (and sanded to finish). The segments were then re-assembled and the "fins" finished to a diameter and the ribs machined to a taper.

My job was to set up the "gang" tools that finished the sides of the inserts. They were individual "high-speed" tool bits (furnished by our tool-grinding section to standard drawings) which I assembled in a holder so several ribs could be machined at a time. A turbine also has packing rings made of a bronze alloy. The cutting tools for these were made of tungsten carbide (Carboloy) which I also was responsible for. The machinists were on "piece-work" which meant they were paid for the work they completed satisfactorily - I was an "hourly" employee, paid (much less) for the hours I worked. Naturally, it was imperative to not hold up the piece-workers by making them wait for tools so I tried to keep ahead of them in completed tool assemblies. There was a small caged area nearby which was a small tool room with only day-shift toolmakers. Equipment was minimal - I remember a surface grinder and band saw, probably not a shaper. I was expected to do some tool work in my spare time but, in practice, it almost never happened.

These many years later names mostly elude me. I became acquainted with a man in the "oil house" section of the back of Bldg. 273. It was a quiet spot where we had many conversations. He introduced me to a young fellow who was the night key-punch operator. At that time computers were in their infancy and information had to be fed to the "IBM's" with cards that had holes punched into them. The cards would be stacked in a holder and the information read from them into the main-frame computer. This fellow (a male secretary, he proudly informed me) had to produce a certain number of cards on his shift to meet his work quota. For a time we three met at the apartment on Union Street of the oil-house man to listen to classical music (I had a reasonable collection as a member of the RCA Victor mail-order club) and enjoy cold-cut sandwiches from makings one of us brought.

In the mean time my number had come up in the Army draft (I had lost my deferment on leaving Navy Ordnance) and I was scheduled to go to Albany for a physical. No sooner had this happened than President Eisenhower ended the draft. I called the Draft Board President and got him to reluctantly rescind my physical (I am sure they wanted to get credit for sending a prospect to Albany for the physical). After about seven months, I was bumped by a toolmaker with 29 years of service (I had 10 at this time). Going to personnel, I could not find a suitable bump so I accepted a third-shift job in Building 60 - Large AC running a horizontal boring mill on piece work. Knowing I would not last on this job, I had decided to take the longest "break-in" possible (6 weeks) to get guaranteed break-in wages and then throw in the towel and leave the company, Going to personnel, I found little choice and ended up on second shift (3:30 PM to 12 Midnight) in the tool room of Building 16 - Large Motor and Generator. It was a struggle to acquaint myself with the work for a rather short time. Off to personnel! They offered me a piece-work job on the "iron-floor" in Building 16 using portable machines.

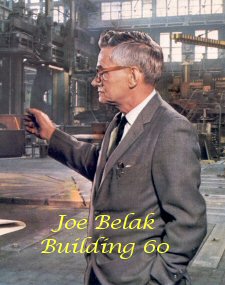

I was not impressed with the job and decided I had come to the end of the line working for GE. I decided to take the piece-work job offered on third shift (11:30 PM to 7:00 AM) in Building 60 - Large AC Generator. It was possible to take a long guaranteed (low) wage break-in (eight weeks) after which I intended to quit. Joe Belak, the day foreman - a person with total decision-making authority over all three shifts, tried mightily to dissuade me from taking the position. He told me I would not last on the job but my mind was made up. He thereupon asked me if I could return the next day. I agreed - and thereby my future was determined! When I returned he took me to their "spring-cage" area and introduced me to Robert Griffin, the operator. Belak said they had too much work for one man and proposed to add me on the second shift. It was a piece-work job which I was destined to remain on through the end of piece-work in 1964, and beyond.

To the left is a cutaway of a typical hydro generator with with the main bearing above the rotor (#1). This is the "spring cage", so-named because of the numerous springs supporting the babbit bearing segments - causing them to "float" and adjust to the "super-finished", very fine polished finish of 5 micro-inch [millionths of an inch], "runner". #2 is the guide bearing also holding babbit segments steadying the rotating shaft. My duties also required me to disassemble these guide bearings, clean all the parts, enlarge the bores in the "test shim" (used to electrically test the insulation value of the segments - leakage would result in erosion of the bearing surfaces), align and re-assemble, fill the bolt holes with epoxy compound and send the support to our boring mills for final machining.Above the spring cage and runner, the very top of the unit, is the exciter: the generator that provides the electrical field for the main generator below.

This is one of the types of spring cages I worked on: laying out the rough- machined parts, drilling, tapping (threading) the drilled holes, cleaning the parts and assembling and aligning the keys (tapered pieces between the babbit bearing segments), dowelling the keys in place (straight precision pins). Then disassembly for final machining of the spring cage surfaces on a vertical boring mill. The parts then returned to my station for cleaning, de-burring the parts and final assembly, inspection and movement to the shipping area for the application of anti-rust coating and boxing for shipment on a railroad flat car. My inspectors were Art Gritzbach, the senior inspector: a grizzled, small man who was very meticulous in his work, and Tom Scrafford, a mild, even-tempered man who nothing could fluster - even a nervous piece-worker like me who approached him (many times) just before quitting time to inspect a job so I could turn in the voucher for my day's pay. I will never forget calm helpfullness.

After some time, work in the spring-cage area declined and my day-man Robert Griffin was given a lay-off notice. I commenced the job by myself on the day shift - 7 AM to 3:30 PM (generally speaking, producion jobs worked on the 7 AM shift while hourly workers started at 7:30 AM., with salaried people on the 8-5 schedule which helped with the traffic congestion. General Electric, at this time, still had a work force in the thousands. As time went on the work load increased with new contracts won. Many GE workers were still not re-called from the earlier lay-off. One of these was a fellow named Bob McGee who knew my foreman Joe Belak and routinely entered the plant looking for a job. Bob, who lived in Carman and was the Chief of the Rotterdam District 3 fire department, "broke-in" with me and made a deal with Belak to stay on days. As partners, we shared duties: Bob was a skilled radial drill press operator and contributed greatly to our earning capacity. For one example, he ordered a marvelous quick-change adapter for the press so we could, with adapters, change drills, counter-bores, and taps with the spindle turning. A great time-saver! In order to have adequate work we expanded into laying-out, drilling and assembling cast iron bearing pedestals. Bob set them up on our electric rotary turntable in a circle six at a time; he would do the drilling and I would replace the finished pieces using our 2-ton jib crane. The piece-work price had been set around World War I and it was very difficult to make a dollar - the secret being in requesting extra money for every defect or excess stock you could find (I made out the voluminous voucher requests).

In the early 1960's work in Large AC Generator was slack and management bid on some jobs out of the ordinary for us to keep us busy. We won a bid on parts for the new Stanford Linear Accelerator, the largest in the world with a two mile length, being built for the U.S. government and managed by Stanford University in California. Bob and I drilled and carefully burred parts made of a very soft steel for its magnetic properties. It was essential that the parts be as defect free as possible because of magnetic stray currents. Unfortunately, they were very easily scratched and dented and we spent considerable time polishing out the defects. Bob McGee, thinking about the problem, entered a suggestion into the GE suggestion system to equip wooden pallets with felt lined pockets for the parts for transportation. It was accepted and he received an award. Typical of the parsimonious nature of the department, we were given felt for the pallets and had to make them ourselves. It worked very well with much less damage to the vital magnet parts. Next to our location, the 42 foot vertical boring mill was set up to wind large spiral coils. The square aluminum material had to be wrapped in insulation and set in a special epoxy plastic; we contributed our expertise in the use of these materials.

Also at this time we worked on parts from Building 50; stainless steel pump castings for nuclear power plants. They were very hard stainless castings with chromium hard spots which made the drilling (and especially tapping) very difficult for Bob, even with the special solvent-based lubricant. Also it was very important not to drill through the wall of the casting. Bob did an outstanding job; my part of the operation was to remove burrs and polish a radius on all the drilled holes because of the possibility of cracks developing from sharp edges due to the high temperatures and pressures of the liquid sodium coolant.

Bob being an officer and now Chief of District 3 had a close friend, Joe Valachovic, on the board of fire commissioners. Joe was also a laison between LAC engineering and the factory. Historically, the control of hydro generators was accomplished mechanically - adequate for the time. Now, however, GE had accomplished the feat of creating high-power diodes and control of generation with solid-state devices was possible. The department set up an experimental facility in part of Building 50 and Foreman Joe Belak agreed to let Bob work on the project part-time. We did a lot of the lay-out and drilling of parts in the spring-cage area so it helped us to keep busy. The project was a smashing success and is now standard design for hydro-generator controls.

| Memoir 1:1932-1947 Birth to Draper HS | Memoir 2:1947-1957 Apprentice to Bldg.46 | Memoir 3:1957-1966 LSTG to LAC |

|---|---|---|

| Memoir 4:1966-1972 LAC to Foundry | Memoir 5:1975-1977 Layout to Toolroom | Memoir 6:1977-1990 Bldg.285 Toolroom |

Original: August 25, 2007; Update 6/18/2008.